The young woman behind the counter at Sunglass Hut did not deserve my wrath. Unfortunately, I only realized this days after I’d stalked out of the shiny store in a huff. At the time I told myself I was justified. I mean…I deserved respect, didn’t I?

I posed some version of this question to my therapist, Carolyn, as I recounted the story a few days later. Arms crossed and urgency in my voice, I still felt resentful about this brief interaction at the mall. Carolyn cocked her head in that small way she had of letting me know my judgment was off.

I was in my early twenties (still new to therapy and it’s jarring reality checks) and I carried a chip on my shoulder that sometimes got knocked off when I felt disrespected. It wasn’t always warranted, though. I know now that many of my perceived slights were stand-ins for actual affronts that occurred in my past. I cringe thinking about the shop clerks and salespeople who put up with my misplaced frustration and anger. Not to mention my ability to personalize corporate policies.

The Sunglass Hut confrontation started with an erroneous belief that I had the right to receive a replacement pair of sunglasses. The chain advertised a warranty from which I somehow got this impression. My shades, which I had purchased at full price on a young person’s budget, were in rough shape from frequent use and a general lack of care. Chalk it up to a shortage of life experience or an unrealistic sense of entitlement, but I walked into the store confident that they would honor my request for new glasses.

My confidence turned to outrage when the self-assured employee looked over my glasses and asserted with a raise of her eyebrow, “I can’t replace these glasses. They look like they have been abused.”

“Abused?!” I asked. I felt my body temperature rising. It struck me hard, this word that felt so unnecessarily strong. Perhaps even accusatory. “They’re not abused,” I answered. My throat tightened. “I just used them normally. I can’t believe you’re not going to honor your own store’s policy!” I stood in front of her, trembling, and waited for her response.

“Sorry,” she said. “We can’t replace these.” She held the sunglasses out to me across the counter. I snatched them from her hand, turned on my heels, and marched out of the store.

Back in Carolyn’s office, she listened to my righteous retelling and affirmed my general desire to speak up on my behalf. She also pointed out that in this instance, the shop worker was simply doing her job and following the store’s rules. My anger, she explained gently, was misplaced. The woman did not deserve the way I had treated her. It was hard to hear at first but she was right, of course. I did deserve to use my voice, that much was true. The problem was that I’d aimed my feelings at the wrong person, and for the wrong reasons.

There has probably always been a mixture of a fighter and a people-pleaser in me. Before I’d been through serious therapy I had shaky self-esteem at best and the fighter side of me could sometimes be unkind. In those moments I said too much, too fiercely, with too little thought for the other person. I remember this with regret now. I also find room to forgive myself. As I often explain to my clients, when we begin to practice asserting the right to stand up and speak with conviction, our early efforts often come out messy.

Growing up feeling stifled, silenced, shut down, and shamed, it takes a leap of faith and courage to override this influence and say your peace. For girls and women, there is an extra layer of social expectation that we “be nice,” stay quiet, and behave ourselves (whatever that means). Early attempts to buck our conditioning will likely come out clumsy and with too much force behind them. We might act like a bull in a china shop and that’s to be expected. The goal is to learn from our actions and take responsibility for them. There truly is no shame in making mistakes.

In my effort to do some light fact-checking for this piece, I googled “Sunglass Hut Warranty” and read up on their policy. The website states, ”This warranty does not cover: scratches on lenses; damages caused by accident, abuse, neglect, shock, improper use or storage of the product; unauthorized modifications or repairs and normal wear and tear.”

Huh.

So it seems the store employee’s use of the term “abuse” was appropriate after all. She was simply naming a specific factor she was required to evaluate. Good for her that she chose not to sugar-coat her assessment for me. I suppose she could have been gentler about it, but that was not her responsibility. And I would be a hypocrite to expect that, given my own gloves-off approach.

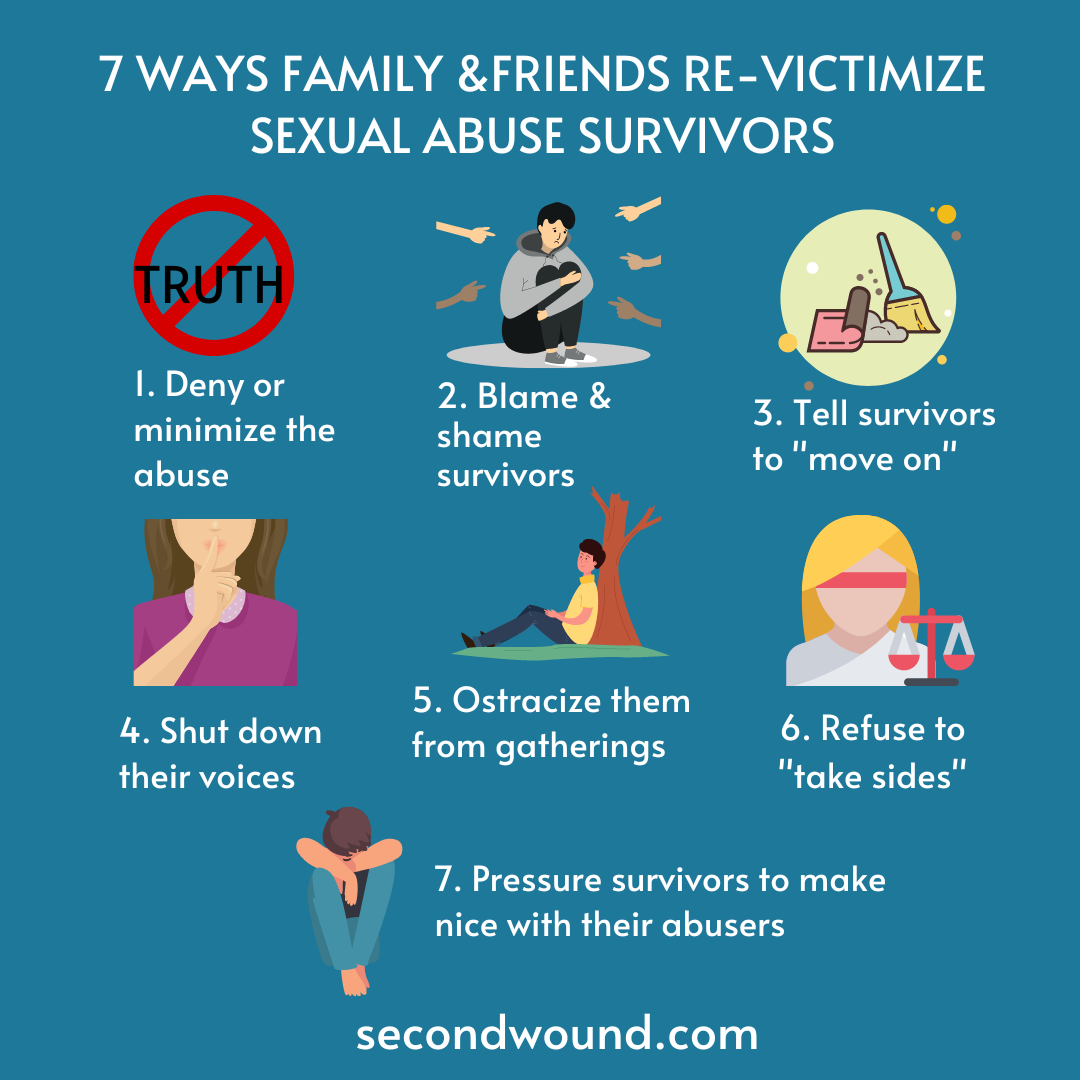

It must be said that the weight of the word “abuse” is not lost on me here. I realize, of course, that the mistreatment and abuse I survived in childhood was at the root of my misguided anger. Carolyn helped me see this. With empathy, support, and the trust she earned during our years together, she led me to explore the effects of my traumatic experiences with understanding and self-compassion. Through this work, my deep-seated shame began to lift and the unresolved anger gradually lessened.

I still get mad sometimes, of course. Despite its bad rap, anger is a useful emotion. It helps us recognize threats and drives us toward useful action. When we begin to speak up and express our thoughts and emotions more fully, some of us start by getting angry at, and fighting, the wrong people. That’s human nature and nothing to be ashamed about. It’s also our job to recognize the problem and consciously direct our anger at real threats instead of perceived ones. With patience, practice, and (ideally) support to work through the very real reasons behind our emotions, we get better at knowing the difference.

It took me a while and the journey was winding and messy. But today I feel far more comfortable advocating for myself, my loved ones, and my beliefs with confidence and compassion. I have learned how to stop paying the hurt forward. Instead, I know how to speak up productively, with the right people, and at the right time. I also take better care of my sunglasses.